Marginalia: “Everybody is a Celebrity”

This series, Marginalia, builds upon a foundation of annotations, taking decontextualized and often disjointed phrases from varied source material and creating something new. Using the lines of others to create a sort of poetry that aims not to be greater than the original, but something viewed from a different angle, under a different light.

The first piece is below, entitled, “Everybody is a Celebrity”

Everybody is a Celebrity:

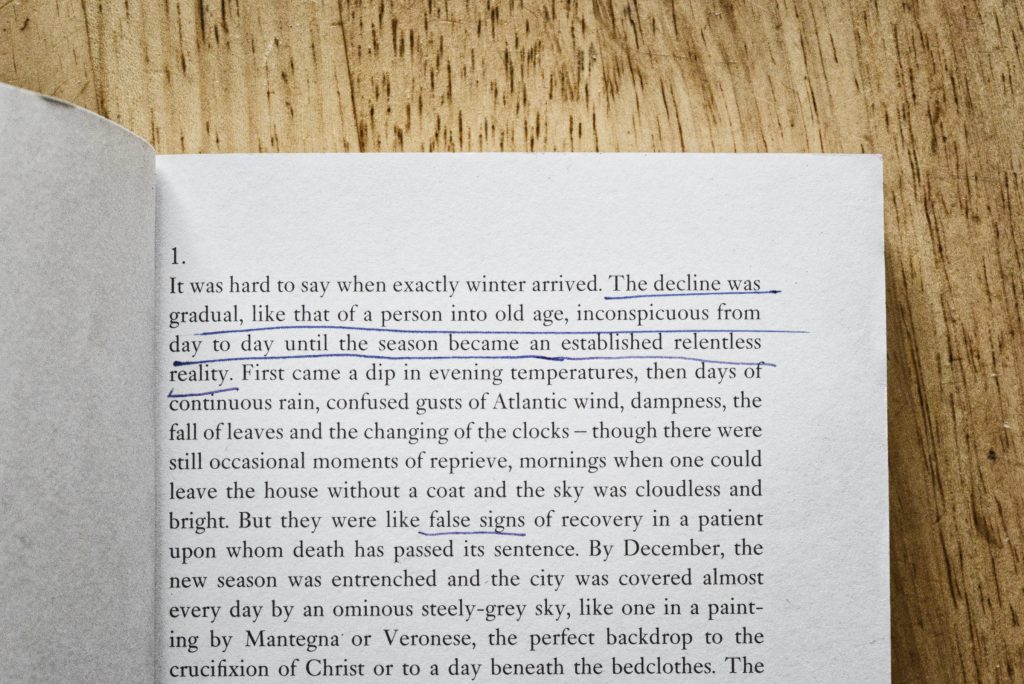

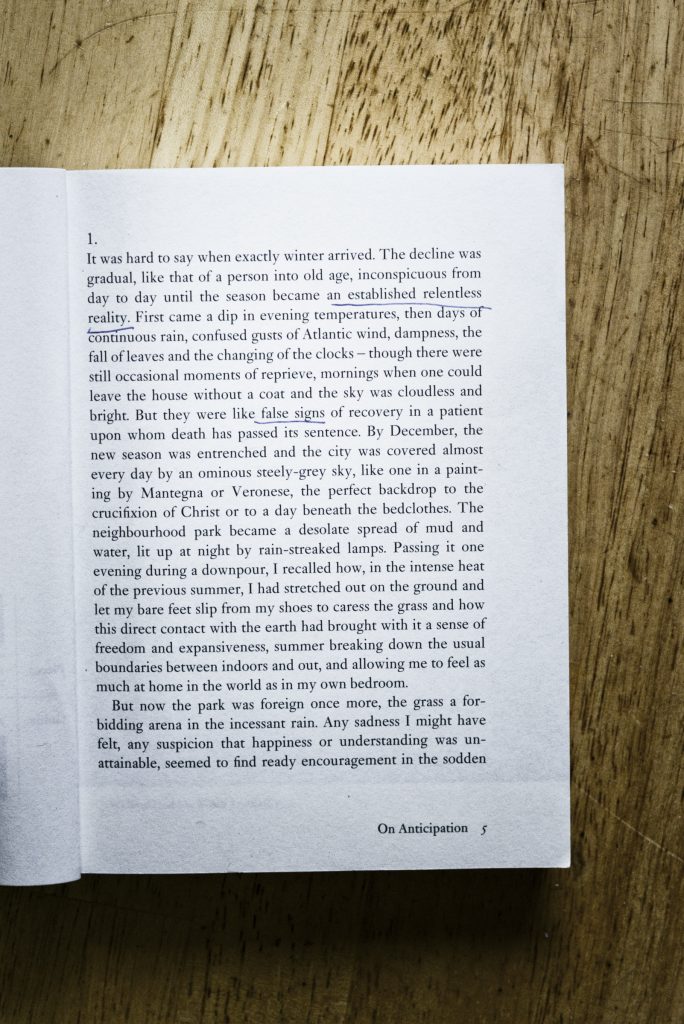

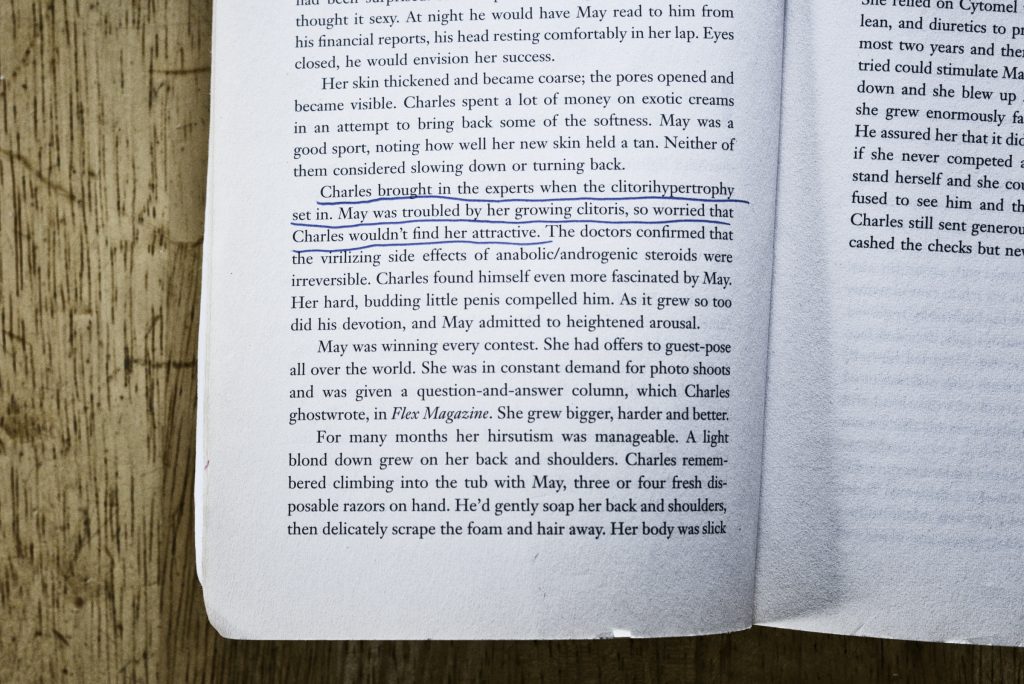

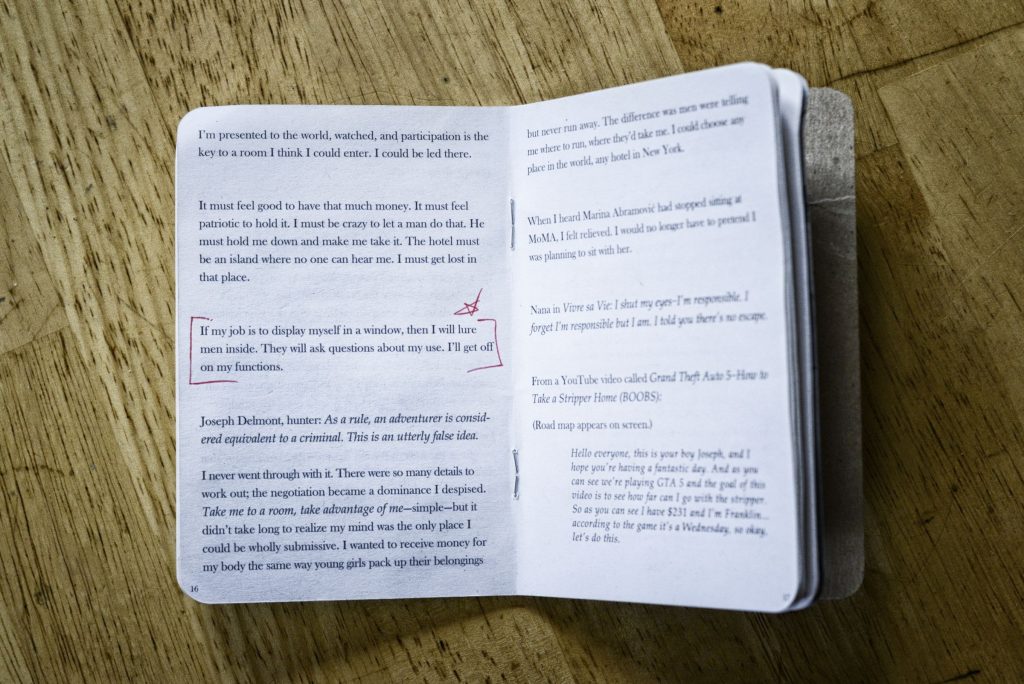

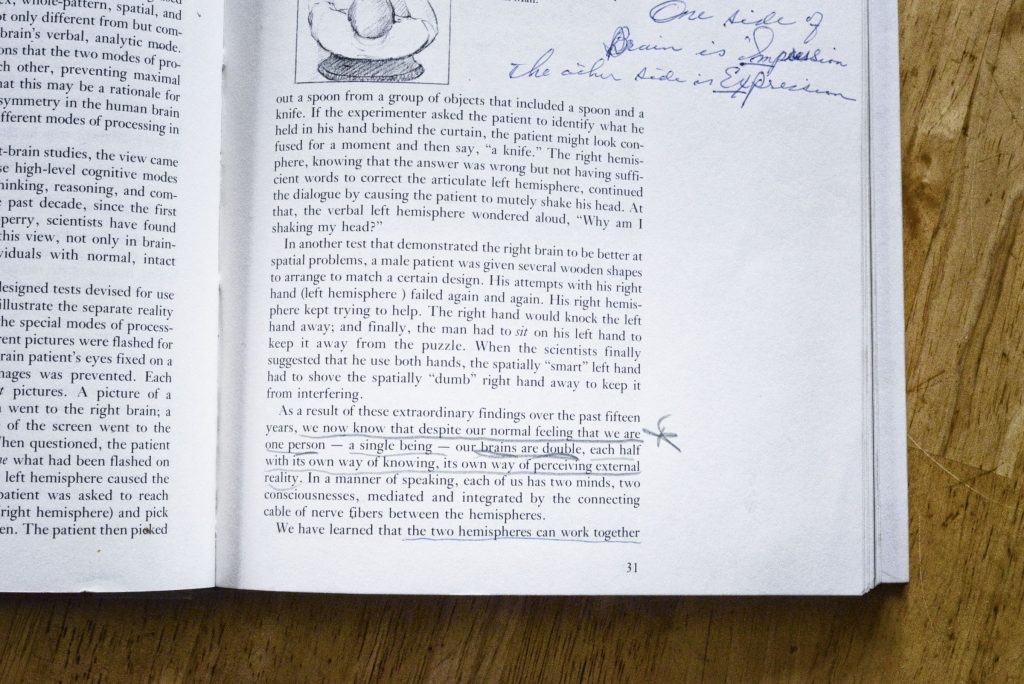

The decline was gradual, like that of a person into old age, inconspicuous from day to day until the season became an established relentless reality. Charles brought in the experts when the clitorihypertrophy set it. May was troubled by her growing clitoris, so worried that Charles wouldn’t find her attractive. We now know that despite our normal feeling that we are one person – a single being – our brains are double, each half with its own way of knowing, its own way of perceiving external reality. If my job is to display myself in a window, then I will lure men inside. They will ask questions about my use. I’ll get off on my functions.

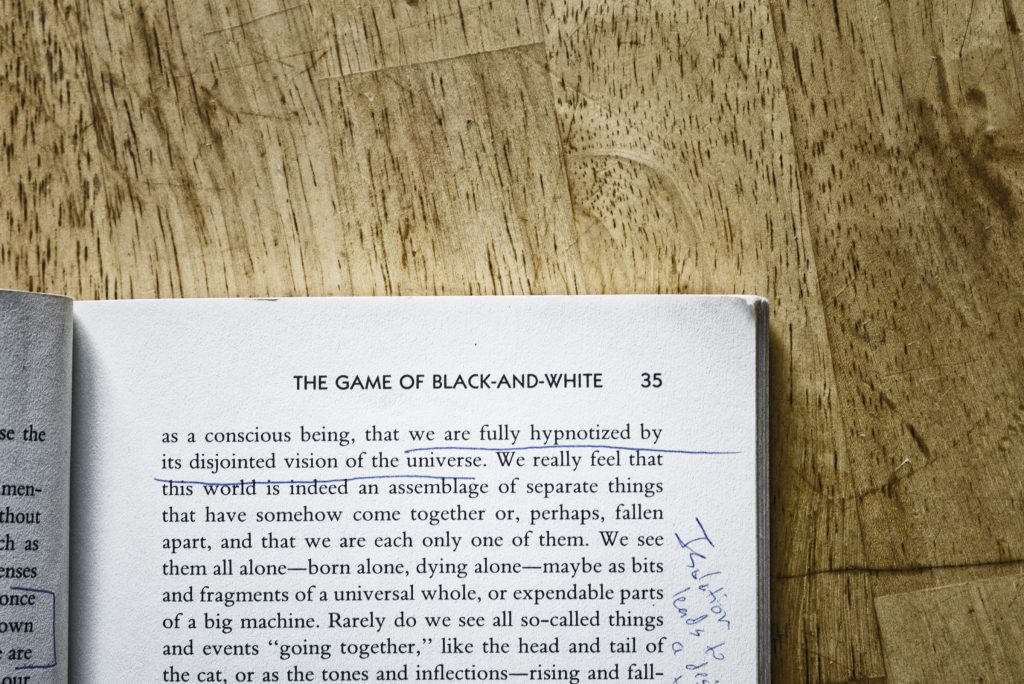

We are fully hypnotized by its disjointed vision of the universe.

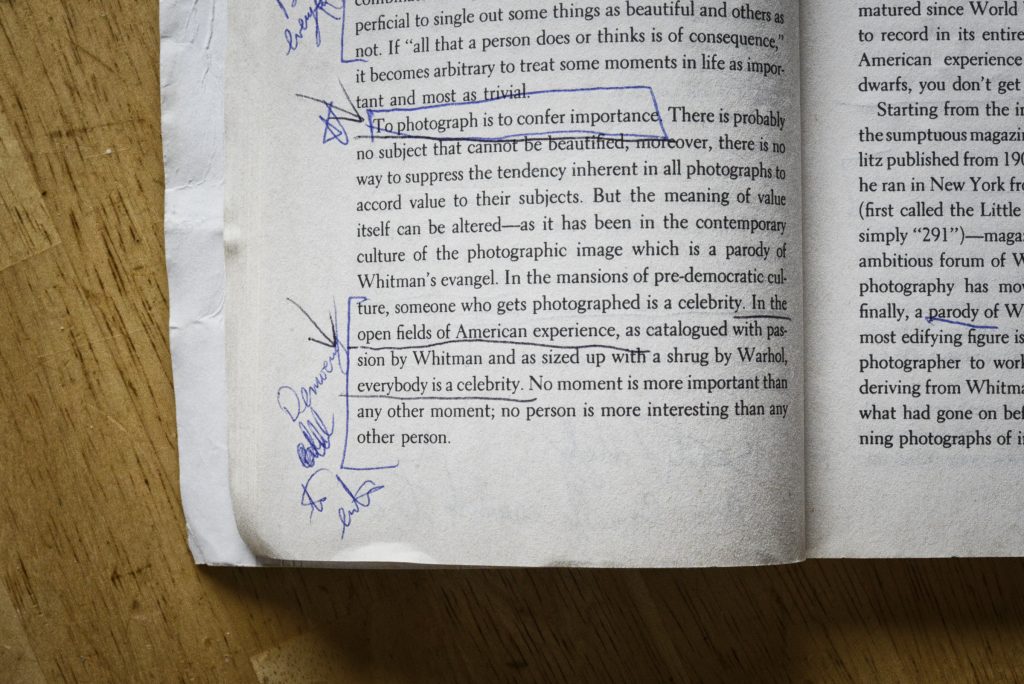

In the open fields of American experience, everyone is a celebrity.

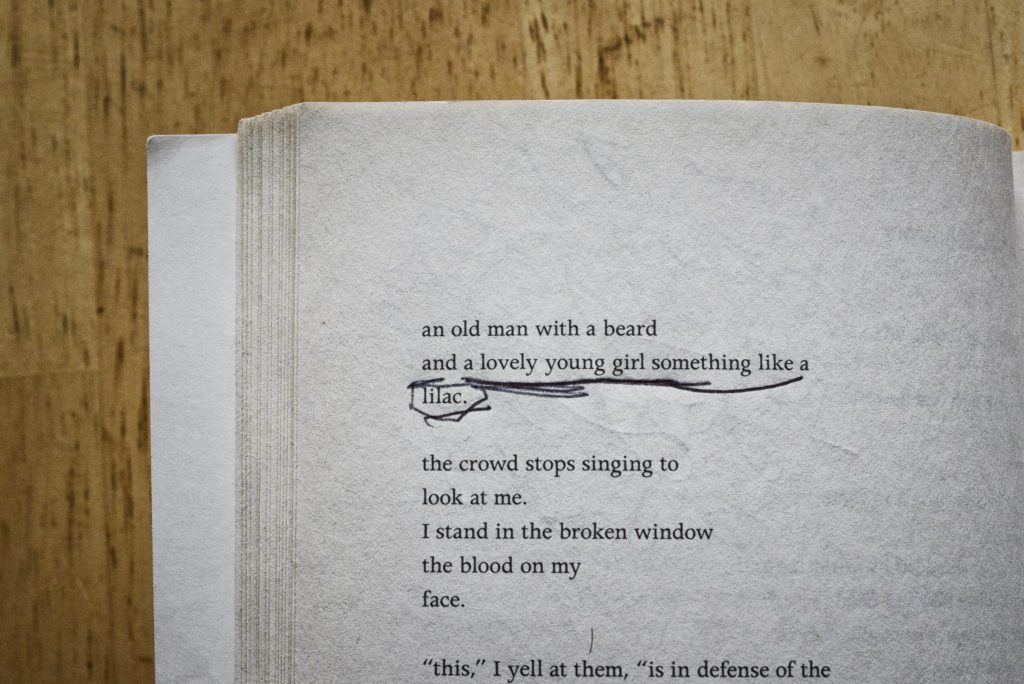

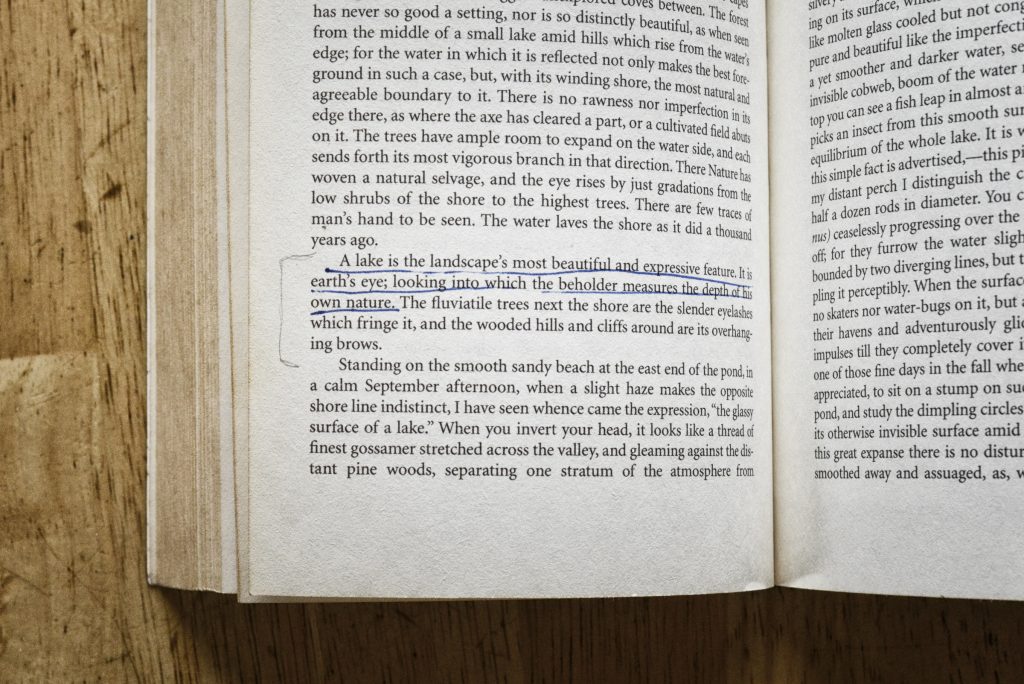

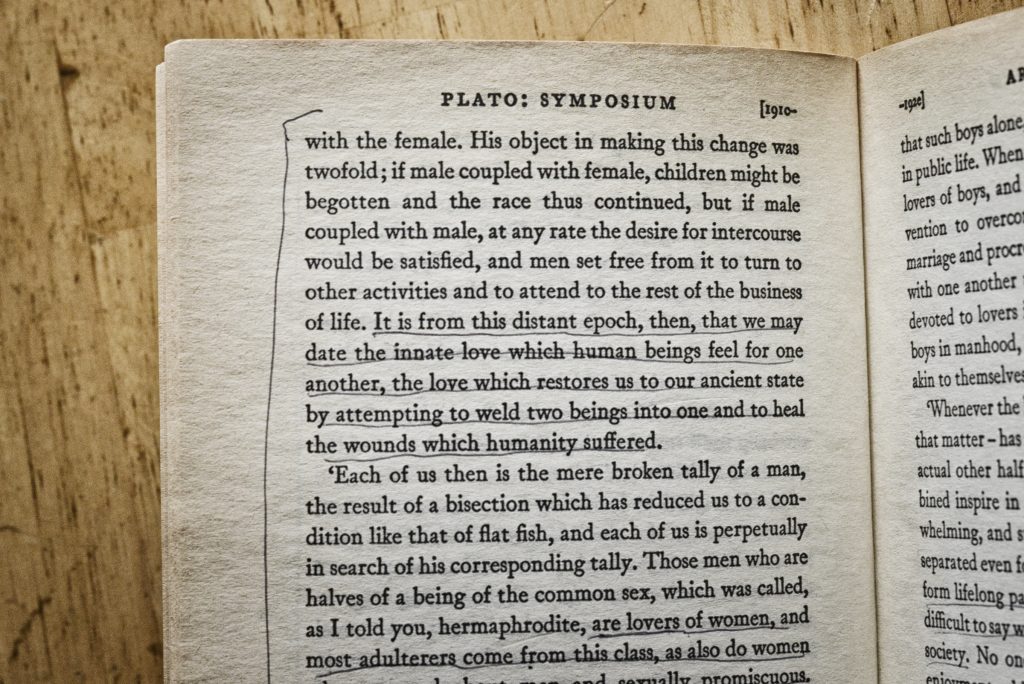

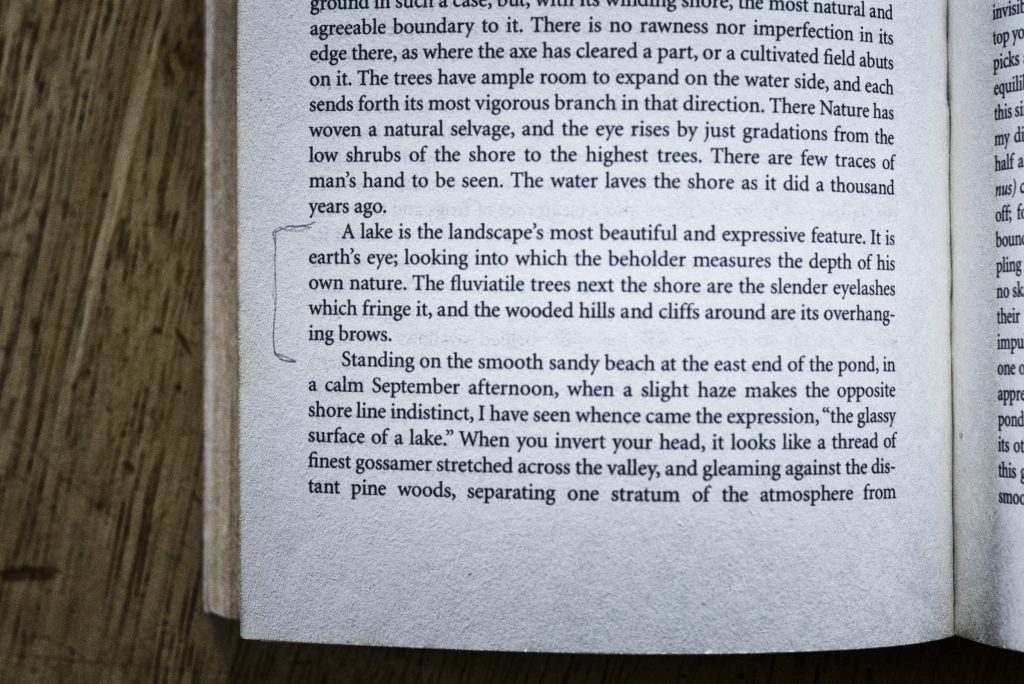

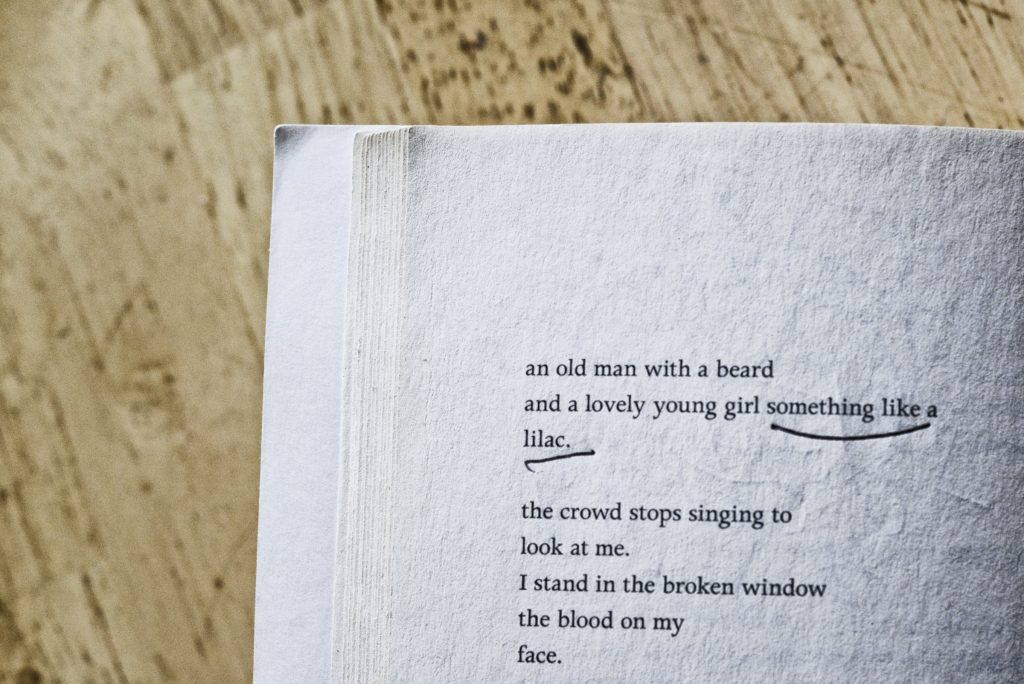

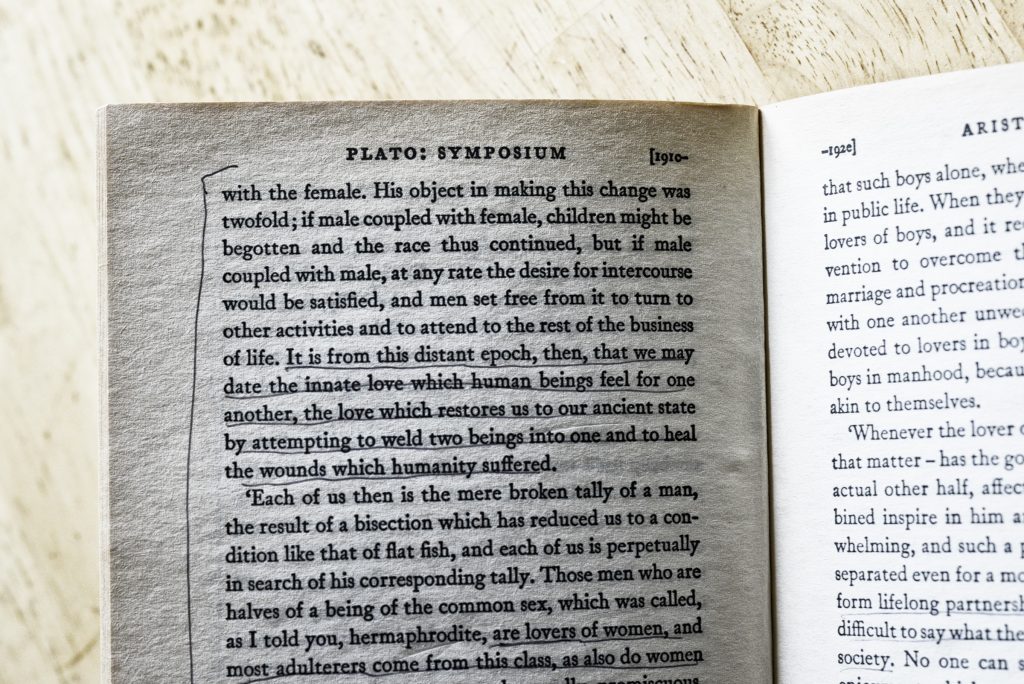

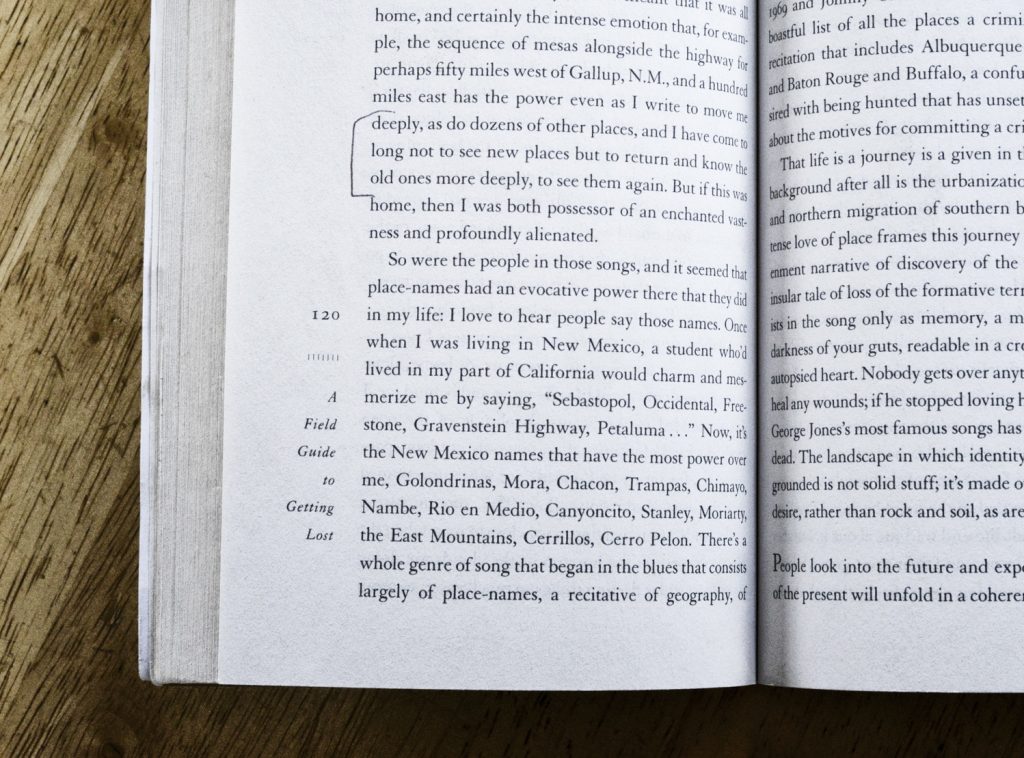

And a lovely young girl, something like a lilac…is the landscape’s most beautiful and expressive feature. It is earth’s eye; looking into which the beholder measures the depth of his own nature. I have come to long not to see new places but to return and know the old ones more deeply, to see them again. It is from this distant epoch, then, that we may date the innate love which human beings feel for one another, the love which restores us to our ancient state by attempting to weld two beings into one and to heal the wounds which humanity suffered.

On the Concept:

“What really knocks me out is a book that, when you’re all done reading it, you wish the author that wrote it was a terrific friend of yours and you could call him up on the phone whenever you felt like it. That doesn’t happen much, though.” ― J.D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye

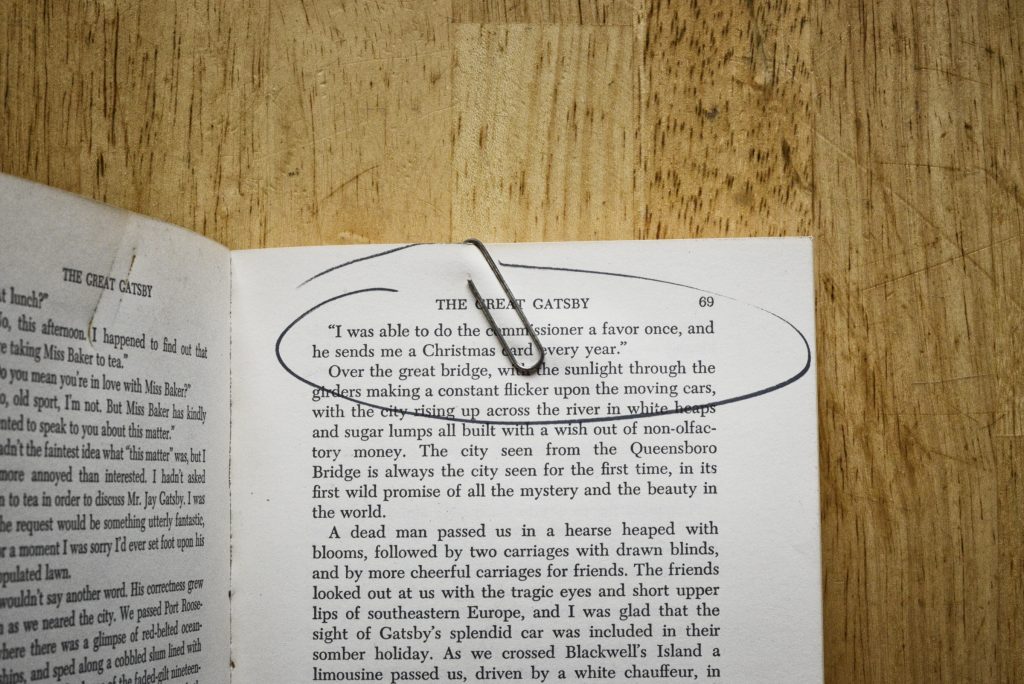

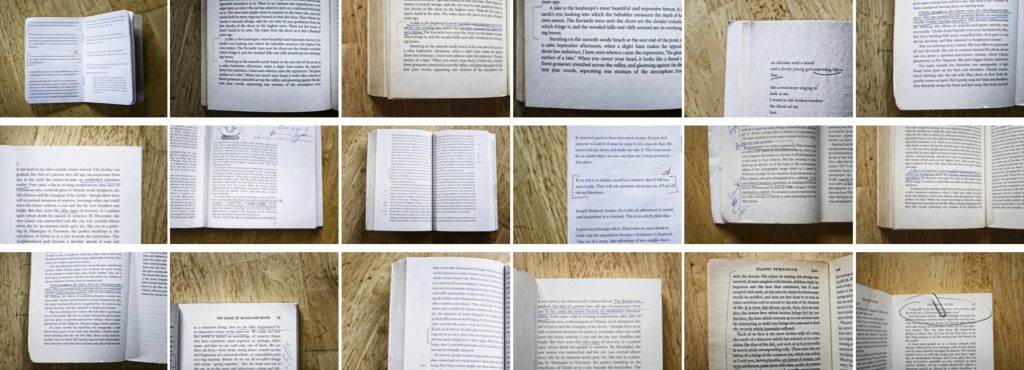

I’ve always been kind of, sort of, a little bit obsessed with finding annotations and other marginalia when thumbing through used books or going through the library stacks. An apt comparison would like finding the Indian Shooting the Star on your Tootsie-Pop Wrapper, an enjoyable rarity rooted in childhood nostalgia. As a child during the glory of the 80’s, I was told never to write in books. It wasn’t necessarily taboo in the sense that it was challenging any longstanding social mores, rather it was frowned upon in the same vein as graffiti or bemoaned as selfies often are now – another indicator that society is going off the rails. Parents and, later, K-12 educators, those ever-staunch guardians of the prim and proper, instilled how marring pristine margins would not only be disrespectful to the content but would become the biggest obstacle to deep reading. I’d lose my focus in the “tagging”. I thought it was bullshit. And, so I did what any questioning, suburban subversive did, I didn’t listen. And I began filling the margins with thoughts and notes, underlining all passages that pulled at me.

I still have some of those old books and the markings are often illegible and, when not, comically simplistic. That is, I seemed to underline things that begged to be underlined. In nonfiction my pencil was anchored to the edges of paragraphs—to topic or conclusory sentences— rarely the meat in the middle. “Yes”, I would think as I underlined some passage, “this is the essence of the thing”, but the reality is I was playing at profundity, not owning it. As my own process of annotation grew, so did my understanding and greater appreciation of the existing ecosystem. When landing on an underlined passage I would predictably halt my reading to stop and wonder who these people are, why they focused on this particular section of the book – what it meant to them, and what it says about them that they chose it. It’s undeniably exciting to see someone’s handwritten thoughts in the edges of a second-hand book. For me, these discoveries often became another narrative within the larger story. All of a sudden, I’m just having a mental conversation with the author, but am having a second dialogue, however asynchronous, with the unknown annotator, attempting to decipher their inner thoughts and the line of their inquiry. Hell, now, I’m just as guilty of marking passages in the hopes that some other soul may one day have an one-way conversation with me.

I’ve long sought to answer a series of questions of my own: what exactly do people find important enough to mark? Are they good at gist-extraction in general? Do “dumb” books have “dumb” underlinings? Do readers underline what they disagree with? How often does something truly excellent not get picked up on by a quorum of readers? Does the rate of underlining degrade over the course of a book? What about first versus middle sentences? A quotation versus naked prose? Simple versus fancy language?Are short sentences more likely to be thought important than long ones? How does the pattern of highlighting compare between nonfiction and fiction, prose and poetry? How do writers highlight? Mathematicians? Baristas? There are never any lasting answers to this study, only an unfolding speculation.

Through this, marginalia became the road to a greater analysis and study of the content before me as well as a deeper understanding of my own evolving emotions. I’ve heard some argue that to hold such conversations is foolish as they exists solely in our minds, but even if they’re a form of mental projection they do create a conversation which didn’t previously exist. Owing to this, I’ve developed an unshakeable belief that this deep reading of beloved material can be the genesis for a deeper compassion, inquisitiveness, and imagination. Indeed, there have been recent studies in neuroscience, psychology, and cognitive sciences which show that “deep reading — slow, immersive, rich in sensory detail and emotional and moral complexity” is a distinctive experience from it’s more staid counterpart which differs in kind and quality from “the mere decoding of words” that constitutes a good deal of what passes for reading today.

In may respects, reading can be thought of as one of the most solitary endeavors, yet when those words you’re reading allow for you to create a mental connection with someone else, how alone are you in those moments? It’s those conversations, with author and annotator, that have long been a draw to reading – who doesn’t intrinsically enjoy using all the colors of their mental palette to complete what is being sketched out?

This series, Marginalia, builds upon a foundation of annotations, taking decontextualized and often disjointed phrases from varied source material and creating something new. Using the lines of others to create a sort of poetry that aims not to be greater than the original, but something viewed from a different angle, under a different light. The conversation and ideas at play here may only exist in this repurposed fashion, they may only exist as a construct from my imagination, but, if I may borrow another well-highlighted phrase…

“Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean that it is not real?” (J.K. Rowling)

Source Material:

- The Art of Travel, Alain de Botton.

- Chemical Pink, Katie Arnoldi

- Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, Betty Edwards

- Pity the Animal, Chelsea Hodson

- The Book, Alan Watts

- On Photography, Susan Sontag

- The People Look Like Flowers at Last, Charles Bukowski

- Walden, Henry David Thoreau

- A Field Guide to Getting Lost, Rebecca Solnit

- The Symposium, Plato